I’ve always preferred being barefoot. Having relatively wide feet I could never find shoes that fit comfortably, and the ability to wear sandals, thongs and other less restrictive footwear year round is one of the things I like most about living in Florida. While more comfortable and less restrictive these aren’t quite the same as being completely barefoot, but are necessary for protection against things like hot asphalt and gravel, crushed seashells, and other sharp, pointy stuff. As much as I would rather not wear shoes at all, having stepped on nails and sliced the bottom of my left foot wide open playing in a field as a child I prefer to err on the side of caution.

I’ve always preferred being barefoot. Having relatively wide feet I could never find shoes that fit comfortably, and the ability to wear sandals, thongs and other less restrictive footwear year round is one of the things I like most about living in Florida. While more comfortable and less restrictive these aren’t quite the same as being completely barefoot, but are necessary for protection against things like hot asphalt and gravel, crushed seashells, and other sharp, pointy stuff. As much as I would rather not wear shoes at all, having stepped on nails and sliced the bottom of my left foot wide open playing in a field as a child I prefer to err on the side of caution.

Thanks to the rise in popularity of barefoot running a few companies and enterprising individuals have started producing “minimalist” footwear, designed to provide some protection for the foot while minimizing the material between the foot and the ground and allowing the foot to work and move the way it is supposed to when standing, walking, running, jumping, etc. While I don’t recommend you take up running for exercise since a proper strength training program can improve general functional ability to a much greater degree in a shorter period of time and with less time in the gym, or for fat loss since it is a relatively slow and inefficient way to eventually burn a very small number of calories, I do recommend switching to more minimalist footwear for the more general health and fitness benefits. If, however, you run for recreation or enjoy competition going barefoot, or almost, is best.

Two of the biggest problems with conventional shoes are the very things they claim as benefits; support and cushioning. The artificial support they provide has an effect similar to wearing a cast, causing the muscles and ligaments of the foot to become weaker over time. If you’ve ever broken a bone and been in a cast for a few weeks you know how quickly muscles can atrophy due to disuse. Restrictive shoes can do something very similar to your feet, and even if you don’t wear them continuously most of us are in some kind of footwear most of the time we’re awake from early childhood on. Whenever people ask about the shoes I wear and question the lack of support I tell them a healthy foot doesn’t require it — if they transition to minimalist footwear gradually their feet will become stronger and support themselves.

Despite the marketing claims of athletic shoe companies there is no evidence that conventional athletic shoe designs with all their air, gels, springs and other cushioning gimmicks do anything to reduce injuries. If anything, all the cushioning is more likely to increase injury. Your foot contains about 200,000 nerve endings which provide feedback necessary for balance, protection, etc., and cushioning dampens your feet’s sensitivity, tending to cause people to plant their feet even harder trying to compensate for lost feedback. Additionally, all the heel cushioning and unnatural stiffness encourages runners to run with a heel strike rather than planting the forefoot, resulting in an increase in impact forces which is greater than the reduction provided by the cushion and affects everything from your heels all the way up your spine. Running barefoot on your forefeet actually results in lower impact forces than running in cushioned shoes and planting your heels.

Shoes which raise the heels significantly can also result in shortened calf muscles and achilles tendons, which may also increase the risk of injury to these during running and jumping. When squatting or deadlifting heel elevation moves the knees further forward increasing the torque around them and can impair balance and reduce the lateral stability of the ankles. During leg presses the knee torque can be reduced by placing the feet higher on the pedal but thick heels still decrease lateral ankle stability. Elevated heels also tend to shift the balance forward which can be a problem during standing exercises. While anecdotal and subjective, I feel my balance and stability is noticeably better when wearing Vibrams or huaraches when squatting or deadlifting (and, contrary to nonsense claimed by “functional training” advocates, balance and stability improve exercise effectiveness).

Shoes which raise the heels significantly can also result in shortened calf muscles and achilles tendons, which may also increase the risk of injury to these during running and jumping. When squatting or deadlifting heel elevation moves the knees further forward increasing the torque around them and can impair balance and reduce the lateral stability of the ankles. During leg presses the knee torque can be reduced by placing the feet higher on the pedal but thick heels still decrease lateral ankle stability. Elevated heels also tend to shift the balance forward which can be a problem during standing exercises. While anecdotal and subjective, I feel my balance and stability is noticeably better when wearing Vibrams or huaraches when squatting or deadlifting (and, contrary to nonsense claimed by “functional training” advocates, balance and stability improve exercise effectiveness).

Also, while anecdotal and subjective, since switching from regular tennis and dress shoes to Vibram Five Fingers in Spring of 2009 a persistent, nagging pain in my left hip (probably the result of lots of running from junior high til early in college) and occasional lower back discomfort from a deadlifting injury in 2004 have disappeared.

Recently, I’ve started wearing huaraches made by InvisibleShoe.com and prefer them to the VFF’s for general wear, as they’re more comfortable and not as weird looking. Wearing their huaraches feels more like being barefoot, and unlike the VFF’s they do not need to be washed every week to prevent them from smelling.

Depending on your feet (Vibrams will not fit correctly on people with longer second toes), intended usage and style preference there are a lot of options for minimalist footwear, ranging from the relatively inexpensive Invisible Shoe huaraches to the more expensive VFF’s and Terra Plana’s Vivo Barefoot. Ideally, whatever you get should be extremely lightweight and flexible with a very thin sole, allow unrestricted movement of the toes, and have minimal support or control elements.

If you need something dressier for work, the Vibram Trek’s with kangaroo leather uppers can pass for dress shoes if people don’t look too closely, and Terra Plana has some nicer looking minimalist footwear. VFF’s are probably the best option if you work out at a gym since most require closed toed shoes for insurance reasons (even though nothing short of steel-toed boots will help if you drop a forty five pound plate on your toes) and their Flow model is specifically designed for water sports. For general wear, working out, walking, hiking, etc., my preference is huaraches since they are the closest you can get to being barefoot while still having some protection against abrasion, cuts and hot surfaces and not getting kicked out of restaurants.

I have two pairs from InvisibleShoe.com, one 6mm and one 4mm. The 6mm’s give a little more protection when walking “off-road” in areas with lots of rocks, branches, etc. but I prefer the 4mm’s the rest of the time. I ordered the 6mm’s custom made (you send them a tracing of your foot following the video instructions on their site) and the kit for the 4mm’s, which includes the soles and cord and instructions for trimming if necessary and punching the hole where the cord starts between the toes, which was pretty straight forward. There are numerous videos on their web site demonstrating the different tying methods, and I chose the “slip-on” method, which was easy to tie, and I can put mine on and take them off without constantly having to tie and untie them.

I have two pairs from InvisibleShoe.com, one 6mm and one 4mm. The 6mm’s give a little more protection when walking “off-road” in areas with lots of rocks, branches, etc. but I prefer the 4mm’s the rest of the time. I ordered the 6mm’s custom made (you send them a tracing of your foot following the video instructions on their site) and the kit for the 4mm’s, which includes the soles and cord and instructions for trimming if necessary and punching the hole where the cord starts between the toes, which was pretty straight forward. There are numerous videos on their web site demonstrating the different tying methods, and I chose the “slip-on” method, which was easy to tie, and I can put mine on and take them off without constantly having to tie and untie them.

My wife and son liked mine and wanted their own so I bought kits and made each of them a pair, using purple cord and a more decorative tying style for hers (also shown on their web site). If you don’t want to make them yourself they’ll make a custom pair for you using a tracing of your feet for a little extra, but I enjoyed making them and while I prefer simplicity and utility if you want to add a personal touch you can incorporate beads, pendants or other decorative elements into the cords, which you can get through their site or your local art supply or crafts store. We’ve been putting a few miles on ours each week walking the dogs and are really liking them.

If you get VFF’s I recommend the Sprints but not the KSO’s. I’ve had a few pairs each of the Classics, Sprints and KSO’s and while I haven’t had any problems with the Classics or Sprints the straps on both pairs of KSO’s have worn through quickly where they pass through the medial eyelet, and I’m not pulling them tight. Contrary to their name, which is an acronym for “Keep Stuff Out” the KSO’s don’t do a very good job of preventing sand from getting inside them and when it does it’s more of a hassle to take them off and put them back on to get it out than with the Classics or Sprints. I have not had structural problems with the other VFF’s and considering how much I wore them before getting my huaraches they were surprisingly durable. The only downside is you have to wash them very frequently to prevent them from smelling, especially if you are working out or running in them, which is a problem a lot of people have been reporting. I can’t comment on Terra Plana or any of the other brands since I don’t own any, but I have tried the Vivo Barefoot on at the store and for the very short time I had them on they were comfortable. If you do try any of the other brands, just remember to look for the qualities mentioned above; lightweight, flexible, very thin sole, unrestricted toe movement, minimal support or control elements.

When making the transition you might want to start slow, a few hours a day at first then gradually increase the time, since some people’s feet take a few weeks to get used to them. Once you get used to them and your feet strengthen a bit you won’t want to go back.

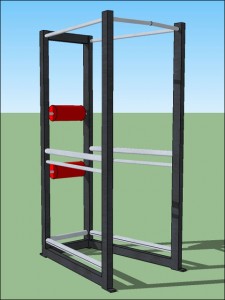

In addition to protecting the cervical spine the muscles of the neck affect your appearance more than you might think. A thick, well developed neck gives you a powerful appearance, while a thin, undermuscled “pencil neck” can make you appear weak and frail. Your neck is also one of the few trainable body parts visible when fully clothed, so while a business suit might conceal most of the results of your disciplined eating and hard work in the gym, you can still impress with a well developed set of sternocleidomastoids.

In addition to protecting the cervical spine the muscles of the neck affect your appearance more than you might think. A thick, well developed neck gives you a powerful appearance, while a thin, undermuscled “pencil neck” can make you appear weak and frail. Your neck is also one of the few trainable body parts visible when fully clothed, so while a business suit might conceal most of the results of your disciplined eating and hard work in the gym, you can still impress with a well developed set of sternocleidomastoids.