Maintaining your health and achieving and maintaining a high level of functional ability should be among your highest priorities. You only live once, and both how long you live and your enjoyment of it are directly affected by your health, your physical capabilities and your appearance.

Proper exercise is a requirement for living the longest, happiest life possible. It is a requirement for self-actualization – realizing your full human potential and necessary for achieving the ideal of a sound mind in a sound body.

While many people have at least some awareness of the potential benefits of exercise relatively few fully realize its importance. I believe at least two of the main reasons for this are failure to associate a lack of exercise with the resulting physical consequences, and underestimation of human physical potential.

It is easier to make cause and effect associations when the cause is one of commission rather than omission and when the time between cause and effect is shorter. The consequences of a lack or omission of exercise are not immediately apparent and in some cases take years. Nautilus inventor Arthur Jones once explained during a seminar:

“If I were to grab you by the throat, and choke off your air supply, it would immediately become apparent to you that oxygen is absolutely essential for life. If I were to lock you in a room with no water, after several hours, the degree of thirst you would experience would indicate to you that water is a requirement for life. If I were to lock you in that room with water, but no food, it would take a little longer, a matter of a couple of days, before you would be ravenously hungry, and there would be no question in your mind that food was absolutely essential for life. However, it often takes years before ones body begins to show the harm done by a lack of proper exercise.”

In the long run, if nothing is done to prevent it, we gradually lose muscle as we age, becoming weaker and more frail and suffering other problems as a result such as decreased basal metabolic rate, decreased insulin sensitivity, increased body fat, decreased cardiovascular and metabolic capacity, increased blood pressure, osteoporosis, increased risk of falling due to reduction in speed and steadiness of movement, etc.

In the meanwhile, if you do not exercise you live with a level of functional ability and a physical appearance far below your potential. Compared to what you can and should be, you are weak, slow, and fragile. If you do exercise, properly, the improvements in strength, speed, durability, and overall health will allow you to do more, do it better, do it longer, and look good while you’re at it. I believe the average, untrained person grossly underestimates their potential, would be surprised at what they are capable of becoming with proper exercise.

Exercise is one of the most important things you can do to improve your life. It deserves the same serious consideration, attention to detail, and effort – both physical and mental – as any other major life goal or achievement of high value. It is not enough to just do exercise, you should strive to master it.

You should perform every exercise and every workout in the safest, most effective, most efficient manner possible.

Safety

It ought to go without saying that exercise should performed in the safest manner possible, but considering the sloppy and haphazard form commonly displayed in gyms and the outright dangerous antics of Crossfit, plyometrics, “core stability training” and similar activities touted as exercise it is apparent most either aren’t aware of or underestimate the potential for injury and long term damage of improper training.

While all physical activity poses some risk of injury exercise can and should be performed in a manner and with a level of control which makes it safer than almost any other activity. It would be counterproductive and downright stupid to perform an activity for the purpose of physical improvement which simultaneously poses a significant risk of causing physical injury or undermining your long term functional ability and health.

This does not mean exercise should be easy. On the contrary, to be effective exercise must involve a high level of effort. There is no conflict between safety and intensity of effort during exercise, however; the manner of performance required to minimize risk of injury is the exact same required to maximize the quality of muscular loading and effectiveness.

Effectiveness

More than any other factor, exercise effectiveness is related to effort, and effort is maximized with proper form. Contrary to claims of some ignorant trainers that how you perform an exercise is less important than the effort you put into it, proper form and maximum effort are not mutually exclusive but directly related. The better your form the higher the intensity.

The histrionics and bodily contortions often associated with a high level of effort during training are not an indication of greater intensity; many trainees commit these discrepancies even when they are not actually working hard. They are attempts to reduce the difficulty of the exercise or distractions from the discomfort of hard work.

The person who grunts, grimaces, and makes a show of heaving or jerking to gain momentum and leaning this way and that to find a lever advantage during exercise is not the one training the hardest, but rather the person who remains stoic as the pain of effort increases, impassive and expressionless, focusing on intensely contracting the targeted muscles while maintaining strict control of the position and movement of their body.

Correct form during exercise involves positioning and or alignment of the body and a path, range and manner of movement designed to effectively load the muscles. Breaking or “loosening” form makes an exercise easier, not harder. Some trainers claim “loosening” form is advantageous because it allows more repetitions to be performed displaying their ignorance of the real objective of exercise.

Efficiency

Exercise is not an end in itself, but a means to improving your health and functional ability to better enjoy other activities and aspects of life. You should spend no more time exercising than necessary for best results. Doing so will not give you better results, but will take away from the finite amount of time you have to pursue other goals or interests and enjoy the company of friends and family. Fortunately very little exercise is required if performed properly and with a high level of effort.

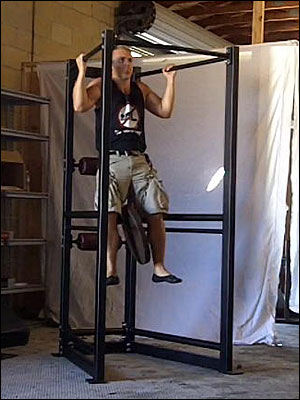

The only exercise you need – in fact the only activity that truly qualifies as exercise – is progressive resistance training. When performed properly it is the safest and most effective method of stimulating improvements in all trainable factors of fitness; muscular strength, size and endurance, cardiovascular and metabolic efficiency, flexibility, bone density and connective tissue strength, and body composition.

The Standard

There are other considerations, but these three – safety, effectiveness, and efficiency – are the highest priorities and the standard against which different methods should be compared if the ultimate purpose of exercise is to contribute to greater enjoyment of life.

There are a lot of training methods, programs, and modalities which can eventually maximize your strength and overall fitness and functional ability.

Any strength training method performed with a relatively high level of effort, consistently, and progressively, and any program that addresses all the major muscle groups without exceeding a volume and frequency of work your body can recover from and adapt to can eventually get you about as strong and as muscular as your genetics will allow.

Any physical activity or combination of activities performed with a relatively high level of effort, over a full range of joint motions, involving loads meaningful to the skeletal system, can eventually result in significant improvements in cardiovascular and metabolic conditioning, flexibility and bone density.

Any modality that provides the ability to meaningfully and progressively load the muscles – free weights, machines, body weight, manual resistance, isometric stations, etc. – can be effective for this purpose if used correctly.

These things are often pointed out to avoid criticizing or making comparisons between methods, however in any objective comparison of different methods of achieving the same goal one will be best.

Your life, your health, and your time, are far too important to settle for just any training method, program, modality. Accept nothing less than the best.

The Mission

My mission is to promote this philosophy, of training in the safest, most effective, most efficient manner possible to maximize life-long health and functional ability with enjoyment of life as the standard, and to teach the best methods of achieving this.

A few weeks ago my brother David and I were talking about fat loss, the nutritional supplement industry, and the difficulty of teaching and motivating people to make positive life changes, especially when it comes to diet and exercise. He related a story I want to share because I hope it will have a positive impact on readers who are currently struggling with fat loss.

A few weeks ago my brother David and I were talking about fat loss, the nutritional supplement industry, and the difficulty of teaching and motivating people to make positive life changes, especially when it comes to diet and exercise. He related a story I want to share because I hope it will have a positive impact on readers who are currently struggling with fat loss.