Since the late 1990’s CrossFit has been gaining popularity as a way of training for “functional” fitness or general physical preparedness. According to the CrossFit web site, CrossFit is,

“…a core strength and conditioning program. We have designed our program to elicit as broad an adaptational response as possible. CrossFit is not a specialized fitness program but a deliberate attempt to optimize physical competence in each of ten recognized fitness domains. They are Cardiovascular and Respiratory endurance, Stamina, Strength, Flexibility, Power, Speed, Coordination, Agility, Balance, and Accuracy.”

The program consists of constantly varying routines incorporating a mix of so-called “functional” movements such as various gymnastic and body weight exercises, plyometrics, Olympic lifts and other compound/multi-joint free weight exercises, and activities like running, cycling and rowing performed for varying durations to target different metabolic pathways. Workouts typically last well under an hour, and the recommended frequency is six days on, one day off.

While CrossFit will no doubt stimulate improvements in fitness, the same or better results can be achieved much more safely and efficiently with a proper, high intensity strength training program.

Speed and Power

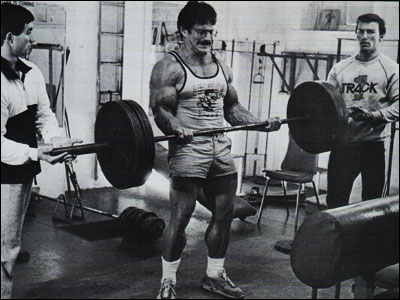

CrossFit places a heavy emphasis on the use of Olympic lifts and other explosive exercises, claiming they are necessary to improve various qualities like power and speed and that these qualities will transfer to other activities. While these exercises will improve power and speed in other activities, it is not because they are performed at high speed or with high power output. It is due to the increases in strength they produce. Strength increases which could be achieved more safely using exercises performed at a more controlled speed of movement and which work the targeted muscle groups more effectively.

Muscular strength can be increased by training at any speed as long as the training is hard and progressive. Regardless of the speed strength is developed at, the more force a muscle is capable of producing the faster it can accelerate a given load, meaning more power production. Even the rate of force development can be improved training at slower speeds, provided the intended speed is fast. If the weight being used is heavy enough, after the first few repetitions of a set a very fast speed will be impossible with strict form. After this point the intent should be to move the weight as fast as possible (without compromising form and offloading onto other muscle groups), although the actual speed will be anything but.

If you train to become as strong as you possibly can you will also become as fast and powerful as you can, regardless of whether you train at fast or slow speeds or somewhere in between. However, you will be less likely to injure yourself using a more controlled speed of movement.

“Functional” Versus “Non-Functional” Exercises

CrossFit training discourages the use of machines or isolation exercises because they believe these are somehow not “functional”. They claim since machine or isolation exercises do not mimic motor recruitment patterns similar to various activities of daily life that they are not “functional” and are somehow less effective at improving functional ability or transferring to improved performance in other activities. This is wrong.

An exercise does not have to mimic the motor recruitment pattern of another activity for the strength gained from that exercise to transfer to it. If you strengthen the muscles involved in performing some activity, performance in that activity will improve regardless of the equipment used or exercises performed. There is no transfer of skill from an exercise to any other movement, no matter how similar. Skill is highly specific. If you want to improve the skill in performing a specific movement or activity, you need to practice the proper performance of that movement or activity. Performing exercises that mimic a movement will certainly develop strength in the muscles involved, but there will be no positive transfer of skill, and no benefit over doing other exercises that effectively work the same muscles.

That being said, free weight and body weight exercises may provide certain psychological benefits that can’t be obtained from machine training. While both are effective for increasing muscular strength, the more concrete experience of free weight and body weight training may provide a better estimate of and confidence in one’s actual physical ability than the more abstract experience of machine training. It is harder to relate the weight you use on a lower back or trunk extension machine to your ability to pick heavy things up off the ground than the weight you deadlift. Certain free weight exercises also teach proper body mechanics for other movements – someone who learns to deadlift properly is more likely to move in a safer more effective manner when picking up other things.

It is also important to consider many commercial exercise machines are poorly designed. While a properly designed machine provides advantages over free weights and body weight an improperly designed machine can reduce the safety or effectiveness of an exercise. You are better off performing free weight or body weight exercises than using machines with incorrect biomechanics, poor adjustability, high friction or other design flaws. Ultimately the equipment you train with is not as important as how you use it, however.

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Conditioning

CrossFit routines often incorporate running, cycling or rowing for cardiovascular and metabolic conditioning. While it is necessary to run, cycle, or row if your goal is to improve the specific skills of running, cycling, and rowing, if your goal is general cardiovascular conditioning high intensity strength training is a better option. During an interview with Dr. Stephen Langer on the show Medicine Man in the early 1980’s, Arthur Jones said,

“…the lifting of weights is so much superior for the purpose of improving the cardiovascular condition of a human being that whatever is in second place is not even in the running, no pun intended. That is to say, running is a very poor, a very dangerous, a very slow, a very inefficient, a very nonproductive method for eventually producing a very limited, low order of cardiovascular benefit. Any, ANY, result that can be produced by any amount of running can be duplicated and surpassed by the proper use of weight lifting for cardiovascular benefits. Now I realize that there are hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of people in this country who don’t understand that, who don’t believe that, who will not admit that. Now these people are simply uninformed. Certainly, it’s possible to run with no benefit, it’s possible to lift weights with no benefit. I’m talking about the proper use of weight lifting; and properly applied, weight lifting will improve your cardiovascular benefit to a degree that is impossible to attain with any amount of running.”

When compound exercises or even simple exercises involving larger muscle groups are performed with a high level of intensity and little or no rest is allowed between exercises the demand on the cardiovascular system can be as high or higher than any other activity performed for the purpose of cardiovascular conditioning. A six-month study conducted at Philipps University in Marburg Germany in 2003 demonstrated equivalent improvements in cardiovascular conditioning between high intensity training using a Nautilus-style circuit routine and traditional cardiovascular training of equal duration and frequency (Maisch B, Baum E, Grimm W. Die Auswirkungen dynamischen Krafttrainings nach dem Nautilus-Prinzip auf kardiozirkulatorische Parameter und Ausdauerleistungsfähigkeit (The effects of resistance training according to the Nautilus principles on cardiocirculatory parameters and endurance). Angenommen vom Fachbereich Humanmedizin der Philipps-Universität Marburg am 11. Dezember 2003).

From a Feb 2005 article on the study in Internal Medicine News,

“A 6-month structured Nautilus weightlifting program resulted in improvements in cardiocirculatory fitness to a degree traditionally considered obtainable only through endurance exercises such as running, bicycling, and swimming, said Dr. Baum, a family physician at Philipps University, Marburg, Germany.

“This opens up new possibilities for cardiopulmonary-oriented exercise besides the traditional stamina sports,” she noted. New exercise options are desirable because some patients just don’t care for endurance exercise, which doesn’t do much to improve muscular strength and stabilization.

A more recent review paper published in the Journal of Exercise Physiology states, “…the key factor in determining physiological adaptations to promote cardiovascular fitness is intense muscular contraction” and that “…these adaptations are, for the most part, a result of resistance training at high intensity (i.e., performed to failure).” (Steele J, Fisher J, McGuff D, Bruce-Low S, Smith D. Resistance Training to Momentary Muscular Failure Improves Cardiovascular Fitness in Humans: A Review of Acute Physiological Responses and Chronic Physiological Adaptations. JEPonline 2012;15(3):53-80.)

Regarding metabolic conditioning, research suggests that while moderate-intensity aerobic training may improve maximal aerobic power it does not improve anaerobic capacity, however high intensity interval training will improve both anaerobic and aerobic performance. High intensity strength training performed with compound/multi-joint exercises for moderate to high repetitions and short rest intervals can be used to accomplish the same goals, along with improvements in muscular strength.

Coordination, Agility, Balance, Accuracy, etc.

Coordination, agility, balance, and accuracy are not aspects of fitness or factors of functional ability themselves, but dependent on the general factors of muscular strength and endurance and specific motor skills.

Coordination is the efficient interaction of different muscle groups in producing movement. Agility is how efficiently and quickly you are able to move and change direction. Balance is your ability to keep your center of gravity over your base. Accuracy is your ability to move with precision. Since all of these are dependent on strength and endurance they can be improved in general by getting stronger and improving cardiovascular and metabolic conditioning. However, coordination, agility, balance, and accuracy in the performance of specific movements involves specific motor skills which are not improved by performing other movements or activities. The extent to which CrossFit or any other exercise program would improve these as general qualities, as opposed to the specific skills of a particular movement or activity is entirely a matter of improving the general factors mentioned above.

Doing CrossFit will improve your coordination, agility, balance, and accuracy more in the specific drills and movements done regularly as part of the workouts, but there is nothing about CrossFit which makes it better than other strength and conditioning methods for improving these qualities in general. The only thing CrossFit is the best at making you better at is CrossFit.

If you are a real athlete or work in a physically demanding profession you should avoid CrossFit to minimize the risk of injuries which can interfere with or prevent you from practicing and competing in your sport or performing your job. If you want to become more coordinated, agile, etc. in the movements of your sport or profession then devote time to learning and practicing those specific skills instead.

Total Conditioning; Faster, Safer and More Efficiently

If your goal is to maximize your functional ability you can do so more quickly, safely and efficiently with a proper high intensity training program following a few basic guidelines:

If your goal is to maximize your functional ability you can do so more quickly, safely and efficiently with a proper high intensity training program following a few basic guidelines:

- Perform one set of one or two exercises for all major muscle groups (favoring compound/multi-joint movements), using a weight which allows for the performance of at least one but not more than three minutes of continuous, slow, strict repetitions.

- Perform each exercise to the point of momentary muscular failure, then continue to contract the target muscles isometrically for five to ten seconds.

- Perform exercises in order of largest to smallest muscle groups worked.

- Move from one exercise to the next as quickly as possible; allow no rest in between.

- Perform no more than three workouts per week on non-consecutive days. Many people get better results training less, depending on individual recovery ability.

- Maximize recovery and adaptation by getting adequate sleep each night, minimizing stress, and eating well (lots of beef, fish, eggs, vegetables, fruit, and nuts, minimize intake of hyper palatable, highly processed foods).