Some critics of high intensity training like to make the claim that “training to failure is training to fail.” However, if you consider the real objective of exercise and what it means to train to momentary muscular failure (MMF) it becomes obvious the truth is the exact opposite; training to failure is really training to succeed.

Your goal when performing an exercise is to impose enough of a stress on your muscles and the systems supporting them to stimulate your body to adapt by improving their capabilities, making you stronger and better conditioned. The more intensely you work – the greater your effort relative to your momentary capability – the greater the stress and the more effective the stimulus for improvement. Your results from exercise are directly proportional to your intensity of effort and have more to do with this than any other training factor, including things like the load used, specific repetition methods, set and repetition schemes, etc.

When you begin an exercise, your intensity of effort is roughly equal to the percentage of your one repetition maximum you are using. If you are capable of lifting one hundred pounds one time in a specific manner, lifting only seventy pounds in the same manner requires only a seventy percent effort at the beginning of the exercise (repetition maximums are specific to the manner an exercise is performed, since different repetition methods, ranges of motion, repetition speeds, etc. can make an exercise harder or easier). As your muscles fatigue each subsequent repetition requires an increasing percentage of your decreasing strength, a greater intensity of effort. When fatigue has reduced your muscles strength enough that the force they are able to exert matches the force of the resistance you are working against and you reach MMF, you are working at maximum intensity.

If you quit an exercise before reaching MMF you may still stimulate improvements in muscular strength and size and other general, trainable factors of functional ability, but not to the same degree as you would if you continued to MMF and worked as intensely as possible. If you quit an exercise before reaching MMF you also will not know exactly how many repetitions you might have been able to perform; you won’t know if you would not have been able to complete another repetition in proper form, or if you could have done one, or two, or even three more. Without this knowledge it is difficult to evaluate changes in performance on a workout to workout basis which can be helpful in adjusting your volume and frequency of training to improve results.

So, several repetitions into an exercise when your muscles are burning, your heart is pounding in your chest, and every nerve in your body is screaming for you to quit, remember it is the last few hardest repetitions of an exercise and especially the very last rep when you achieve MMF that matter most, and ask yourself what is more important? Making the best possible progress towards your training goals? Or avoiding the momentary discomfort of continuing the exercise?

What does training to MMF really train you to do? It trains you to persevere through pain and discomfort to achieve your goals. It trains you to work even harder when things get tough, instead of quitting. It trains you to be stronger mentally as well as physically and builds even greater self-discipline that carries over to everything else you do. Training to MMF does not train you to fail; it builds and strengthens the traits that allow you to succeed.

Not training to MMF trains you to give up when things get uncomfortable. Not training to MMF trains you to avoid hard work. Not training to MMF trains you quit at something when you should be giving it everything you’ve got instead. Not training to MMF is what really trains you to fail.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Excellent article and reminder about the importance of training to momentary muscular failure, Drew! I recently read another good article on this topic over at T-Nation (believe it or not!), which came to the same general conclusion about training to failure. However, it cites a study (Cameron J. Mitchell et al. J Appl Physiol 2012;113:71-7) indicating that 3 sets to failure produces greater hypertrophy than only 1 set to failure.

“In the study, having three ‘failure triggers’ caused more hypertrophy than having only one failure trigger. And as long as you had those triggers, the hypertrophy was the same regardless of the weight lifted.” — https://www.t-nation.com/training/single-best-muscle-building-method

Check out the article and see what you think. I’ve also recently been experimenting with increasing the volume of my training by performing several not-to-failure sets followed by one final set to failure with a slightly reduced weight. For example, I may do 3 sets with 275 lbs on the Hammer Incline Press stopping a rep or two shy of failure, followed by 1 final set to failure with 250 lbs. This usually keeps me within the 8-12 rep range on all sets, which is the rep range that seems to work best for me. So far I feel that I’ve been recovering fairly well by doing this, and I’m still able to get in and out of the gym within about an hour. However, I’m pretty sure that performing 3 sets to failure on a full-body routine would simply be too exhausting and difficult to recover from, so I doubt I’ll be trying that protocol anytime soon!

Hey Roger,

I’ve discussed many of the problems with studies like this in Thoughts On Relative Volume Of Single And Multi-Set Workouts and why the proper measure of exercise volume is force over time and not sets and reps, and how most research shows no significant difference between performing single and multiple sets in the Evidence Based Resistance Training Recommendations series.

This is why I recommend using repetition ranges which average around one minute of time under load as a starting point for most people; both load (tension) and duration (metabolic stress) are important. If a set is too short, like most sets performed at conventional rep speeds taking only around twenty seconds, you sacrifice duration for tension. If a set is too long, like the three to four minutes some SuperSlow trainers use, you sacrifice tension for duration. In the long run the cumulative volume and intensity is probably far more important than whether or how it is split up (e.g. 1×12, 2×6, 3×4, etc.), so a few brief non-failure sets followed by one set to failure (similar to what Mike Mentzer used to recommend) would work, but a single continuous set to failure for an equivalent duration is more efficient.

The detractors of training to momentary muscular failure are confusing strength training with skill rehearsal. Continuing to rehearse a skill after debilitating fatigue has set in is counter-productive. Together, strength-training to MMF, and _not_ rehearsing skills to failure, adds-up to the best possible performance of skills when fatigued during competition.

Hey Mark,

This is correct, and one of the reasons it is important to distinguish between an exercise and a competitive lift. The proper way to squat, bench, or deadlift for exercise is very different than the proper way to squat, bench, or deadlift for competition because the goals are completely different. The goal of exercise is to efficiently load the target muscles to impose a stress for the purpose of stimulating an adaptive response, and is best done in a manner that makes the weight as hard as possible to lift. The goal of a competitive lift is to be able to move as much weight as possible and is best done in a manner that makes the weight as easy as possible to lift. As I mentioned in the recent e-mail newsletter, “…the people saying (training to failure is training to fail) are often doing so out of context and confusing the goal of performing an exercise to stimulate improvements in strength with the goal of practicing a competitive lift to improve skill, which are very different things.”

Great post! For the most part of my training years I have trained by myself. Although I always train to failure I have always been curious if I have been doing it right. You mentioned in one video I saw on youtube ( I think it was one of those 21 convention seminars) that in order to ‘learn how to train to failure’ you must train under some trainer experienced with HIT. That being said, I think it will be a great idea to show how exactly you go to failure and what true MMF is. Now that you have been posting videos on your blog, I think a lot of your followers would learn greatly from watching a video on this subject.

Hey Anthony,

It is not necessary to train under an experienced HIT trainer to learn to train to MMF, but a good trainer can teach you how to do so more safely and efficiently and can motivate you to train more intensely.

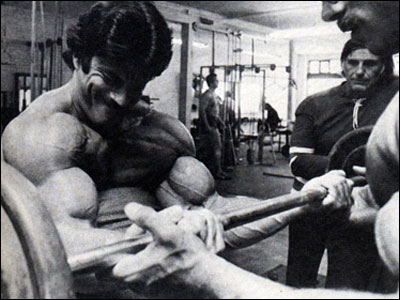

A video demonstrating training to MMF probably wouldn’t be very helpful, except maybe to show what not to do, since the only thing that should change when MMF is achieved is that positive movement becomes impossible. All the grunting, screaming, grimacing, contortions, and other histrionics often displayed by people pretending to train intensely are nothing but show and should be avoided.

In My Philosophy of Exercise I wrote,

“More than any other factor, exercise effectiveness is related to effort, and effort is maximized with proper form. Contrary to claims of some ignorant trainers that how you perform an exercise is less important than the effort you put into it, proper form and maximum effort are not mutually exclusive but directly related. The better your form the higher the intensity.

The histrionics and bodily contortions often associated with a high level of effort during training are not an indication of greater intensity; many trainees commit these discrepancies even when they are not actually working hard. They are attempts to reduce the difficulty of the exercise or distractions from the discomfort of hard work.

The person who grunts, grimaces, and makes a show of heaving or jerking to gain momentum and leaning this way and that to find a lever advantage during exercise is not the one training the hardest, but rather the person who remains stoic as the pain of effort increases, impassive and expressionless, focusing on intensely contracting the targeted muscles while maintaining strict control of the position and movement of their body.

Correct form during exercise involves positioning and or alignment of the body and a path, range and manner of movement designed to effectively load the muscles. Breaking or “loosening” form makes an exercise easier, not harder. Some trainers claim “loosening” form is advantageous because it allows more repetitions to be performed displaying their ignorance of the real objective of exercise.”

One of the things I like about HIT is that failure *is* success. For me that is an invaluable life lesson, and I think coming face to face with my limits every time I train has been good for me. By doing this I hope to become more accepting of myself and more realistic with my expectations of myself.

A possible problem with it is that I wonder if everyone is psychologically capable of doing it. I wonder if I would have been capable of doing it earlier in my life.

Hey James,

That’s why I often describe it as “achieving failure” rather than “hitting failure” or “reaching failure.” In the case of exercise, failure really is success.

Like most things, people vary in their ability to push themselves through discomfort and pain, and there are people out there who will have a much harder time training to momentary muscular failure than others. Ultimately, how hard a person is willing to work comes down to how badly they want what they’re working for, and that’s why I emphasize end goals over means goals when talking with people about motivation for training.