Question: What do you recommend if I want to do high intensity training for bodybuilding and not just strength or general fitness?

Is a higher repetition range better for hypertrophy?

Do I need more variety of exercises to make sure I’m working all my muscles from different angles or in different parts of the range of motion?

How can I tell where I need the most work and what can I do about lagging muscle groups?

Answer: Contrary to popular but uninformed opinion there is no difference in how you should perform exercises for increasing muscular size versus muscular strength, and you do not need a large variety of exercises for any muscle group. However, there are some differences in how you should design your workouts for bodybuilding versus general strength and conditioning.

Training for Strength vs Hypertrophy

Many people confuse strength, which is your muscles’ ability to produce force, with how much weight you are able to lift in a specific exercise, which is a combination of your strength, how skilled you are in performing that exercise (skilled at the assumed objective of lifting the weight, as opposed to the real objective of using the weight to efficiently load and fatigue the target muscles), and specific neural adaptations. Strength is general, meaning it transfers to every physical activity you perform. Skill and specific neural adaptations do not transfer to other physical activities, only the activity or exercise practiced. This is one of the problems with using 1RM testing to compare the effect on strength of different training methods, especially when the same exercises are used for workouts and testing.

The old belief that different repetition ranges were required to stimulate different types of adaptations (e.g. lower reps for strength, medium for hypertrophy, high for endurance) is based on observations of how bodybuilders versus powerlifters tended to train, without consideration for genetic differences and selection bias. We now know this belief was wrong, and a very broad range of repetitions (time under load, actually) can be similarly effective for increasing both muscular strength (general) and muscular size when exercises are performed to momentary muscle failure.

If your goal is to improve your 1RM in a specific exercise you would benefit from also practicing that exercise with a very heavy weight and very low reps with unrestricted speed of movement. For general increases in muscular strength and size, though, a broad range of loads and repetitions will work, and longer sets with more moderate loads will be safer as well as better for metabolic and cardiovascular conditioning, which is also important.

For more on this, read Q&A: High Intensity Training for Strength vs Size vs Power and The Myth of Training for Sarcoplasmic Versus Myofibrillar Hypertrophy and High Load/Low Reps Versus Low Load/High Reps For Hypertrophy.

The Need for Non-Variation in Exercise

As for variety of exercises, although our bodies are capable of an infinite variety of movements all of these are just combinations of a relatively small number of basic joint movements, and only a few basic exercises are required to effectively work all the major muscle groups which produce them. Just because a particular muscle is capable of producing more than one joint movement doesn’t mean you need to work that muscle through all of those movements, either, just one is enough. Even convergent muscles capable of producing movement in very different planes can be worked effectively with just one or two.

You are better off performing just one or two of the best exercises for each muscle group—the most effective and safest you are capable of with the available equipment—consistently, than performing a wide variety or frequently changing them. Read The Ultimate Routine for more on this.

Exercise Selection for Bodybuilding versus Functional Ability

For general strength and conditioning, to improve your overall functional ability, your workouts should be designed to strengthen every major muscle group as much as possible, which will eventually result in the maximum size of every muscle group your genetics will allow. However, most people do not have the genetics for perfectly proportional and symmetrical growth throughout the body, and will tend to have some muscle groups with greater or lesser potential for strength and size than the others. This difference in the relative size potential of different muscle groups doesn’t matter much if your only concern is maximizing your potential physical performance and not having a perfectly proportional physique, but if aesthetics are a higher priority for you, you need to be careful to avoid over-development or under-development of muscle groups with greater or lesser size potential.

This is not as much about how you perform your exercises as it is about which exercises you include in your workouts and how you organize them.

It is rare to not want a muscle to get bigger, but bodybuilding isn’t just about size, it is also about proportion, shape, and symmetry. If you have a particular muscle group that grows too large relative to the others, it can negatively affect your proportions or overall shape. Reducing the size of a disproportionately developed muscle group or not letting a fast-growing muscle group get ahead of the rest of your physique is relatively easy. If a muscle group is too big stop training it until reduces to a size proportional to the rest of your body. If a muscle group’s growth is outpacing the growth of the rest of your body, stop working that muscle group to failure and do not increase the weight you use for that muscle group until the rest of your body has caught up.

If you normally work the over-large muscle group with a compound exercise, you will need to substitute simple exercises instead to work it separate from the other muscles (e.g. a pullover and arm curl instead of a pulldown or chin-up, a lateral raise and triceps extension instead of an overhead press, or a hip extension and a leg extension instead of a leg press or squat.)

Increasing the size of lagging muscle groups obviously requires a different approach, but not the one most assume. The key to body part specialization is not performing a larger volume of work for the target muscle groups with pre-exhaust or more varied exercises, or working them “harder” with forced-reps, drop-sets, rest-pause, finishing negatives or other set extension techniques, because more volume and/or more time spent performing an exercise past failure will not stimulate a greater increases in strength and size, it will only place greater demands on recovery energy and resources leaving less for growth. Instead, the key to designing a specialization workout for a body part or muscle group is to cut out exercises for all other muscle groups, to eliminate competition for your body’s limited energy and resources for recovery and growth.

You should focus on specializing just one body part or one to three smaller muscle groups at a time—whichever are lagging the most. For example, if your upper arms were lagging, a specialization workout would consist of just one set of one direct, simple exercise for each; one elbow extension exercise and one elbow flexion exercise. Nothing else. You can alternate a specialization workout with your regular workouts, or, if the lagging body part is very stubborn, perform only specialization workouts for three or four weeks before alternating your regular workouts with the specialization workout for as long as it takes the lagging muscle group to catch up (assuming your genetics allow it to).

When you add a specialization workout to your program you should maintain the same workout frequency, rather than add another weekly workout. For example, if you normally do two full-body workouts per week (a good starting point for most), start by alternating between your regular workouts and the specialization workout. After two or three months of this the lagging body part or muscle groups should have improved significantly (assuming they still have the potential to get larger) and you can cut back to performing the specialization workout every third or fourth time.

Evaluating Physique Improvements

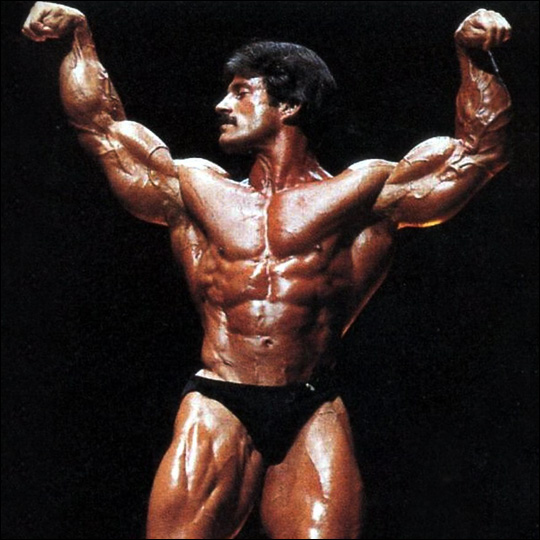

Physique evaluation is rather subjective compared to evaluating improvements in exercise performance, but you can compare the progress of individual body parts by performing regular circumference measurements and you can evaluate your overall physique by photographing or taking a short video of yourself going through the mandatory bodybuilding poses and a few of your favorites every six to eight weeks (same place, same camera position, same lighting every time) and getting feedback from your trainer or training partners:

- Front Lat Spread

- Front Double Biceps

- Side Chest

- Rear Lat Spread

- Rear Double Biceps

- Side Triceps

- Abdominal and Thigh

- Most Muscular

Save your images or videos in folders with the date they were taken or recorded. When you have two or more sets of photos or videos you can compare the before and after side by side. Keep notes on your training charts or in a journal on your progress, including how changes in your circumference measurements affect your appearance. Use yours and others’ feedback on these to determine what muscle groups may need either detraining or specialization, and adjust your workouts accordingly.

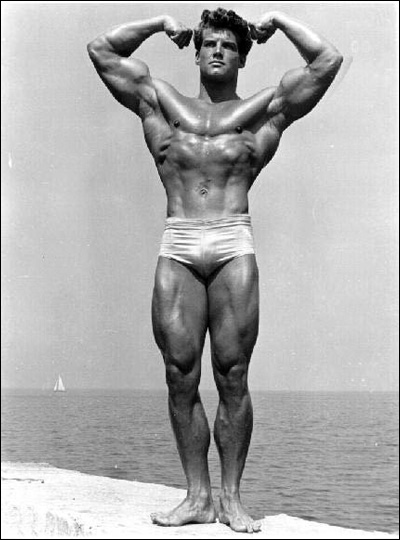

If you want a more realistic standard to compare your physique against than today’s competitive bodybuilders—and one generally considered to be more aesthetically pleasing—look for photos of golden age bodybuilders like the one above of Steve Reeves, Mr. Universe 1950, performing a front double biceps pose. Keep in mind those bodybuilders were still very genetically gifted, but developing a physique like theirs is still well within the realm of possibility for some drug-free trainees.