The recent review by James Fisher, James Steele, Stewart Bruce-Low and Dave Smith should be on the “must read” list for everyone with an interest in exercise. In fact, you should download and read it before you read the rest of this post which is the second of several commentaries I will be writing on their review.

Click here to read part 1 on anti-HIT bias, intensity and one rep max testing

Momentary Muscular Failure

Momentary muscular failure (MMF) occurs when your muscles become too fatigued for you to continue an exercise in the prescribed form. Several arguments have been made for training to failure, most originating with Nautilus inventor Arthur Jones.

1. There is no way to know the exact level of intensity required to stimulate maximum muscular strength and size increases. There is also no way to accurately measure intensity of effort during exercise except when one has reached MMF, at which point the intensity (the percentage of your maximum momentary capability you are working at) is 100%. The only way to know you have trained intensely enough to stimulate the maximum possible response is to perform an exercise to the point of MMF.

2. Optimum long term progress requires adjusting the volume and frequency of your training to your body’s response to exercise. Part of this is being able to compare exercise performance between workouts. If you do not perform an exercise to failure there is no way to know how many repetitions or seconds of time under load you could have done, so there is no way to objectively compare your strength between workouts.

3. Motor units are recruited in order from smallest to largest. Over the course of an exercise as smaller motor units are fatigued, more and larger motor units are recruited to maintain the required level of force (until all the motor units are recruited at which point rate coding is increased to maintain force output). The motor units with the greatest potential for strength and size increases are the last to be recruited. Training to MMF ensures you have recruited all of the motor units, including the high threshold ones.

All the studies comparing training to MMF with training submaximally showed training to failure produced results that were equal, better, or more efficient (required only 30% of the time). While it is possible to get good results from training without consistently working to failure as long as it is done progressively (in which case MMF will occur at least occasionally), and while all the motor units in a muscle will be recruited before reaching MMF with typical loads and rep ranges, if you want the best possible results you should go to failure on each exercise.

Criticisms of Training to Failure

Most criticism of training to MMF is actually blame for other things. Some people blame training to MMF for overtraining, calling it “CNS “burnout” (the CNS and immune system are both part of the response to chronic overtraining). There is nothing about training to failure in and of itself that would cause this. What is more likely is they did not compensate for the increase in training intensity when switching to training to MMF by reducing their training volume appropriately. As long as the overall training volume and frequency are not excessive for an individual there is no reason training to MMF alone would cause overtraining or any related effects.

Some people claim training to MMF is dangerous, which is nonsense. An injury occurs during exercise when a tissue is exposed to an excessive level of force, either due to rapid acceleration or by moving into a position resulting in too much compression or stretching. As long as an exercise is performed in a smooth and controlled manner, without any quick, bouncing, jerking, or yanking movements, and as long as the correct positioning and movement is performed and proper safety equipment used when necessary, there is nothing about training to failure that will harm a person.

One of the more ridiculous claims is “training to failure is training to fail”, and that by performing an exercise to MMF you are conditioning yourself to expect to fail in other activities. While it makes a nice, neat soundbite for those opposed to training to MMF, it is based on the erroneous assumption that the goal of an exercise is to lift the weight (or move against whatever type of resistance you’re working with). The real goal is to work the target muscles as intensely as possible to stimulate an adaptive response, and lifting a weight or moving against some other form of resistance is just a means to that end. When you have achieved MMF you have succeeded in the real goal of exercise. If anything, training to MMF teaches you to work as hard as possible and give 100%, while submaximal training teaches you to quit when things start to get really hard.

Part 3: Rating of Perceived Exertion and Load and Rep Range

Comments on this entry are closed.

You equate MMF to the inability to continue an exercise…but I guess I’m curious how a trainee knows that the apparent “failure” is muscular and not mechanical, i.e. hit a point of noticeable disadvantage on a machine or free weight movement?

Are there other indicators of maximal effort that should be sought after and qualified other than, “I can’t go anymore”?

Hey Joe,

If you’re using a properly designed machine or performing a free weight or bodyweight exercise correctly the strength and resistance curves will be congruent enough that when you fail, even if it is at a “sticking point”, you will still have efficiently and effectively stimulated the muscles involved. Unless a machine is designed or exercise is performed in a manner resulting in a huge sticking point and providing little resistance over the rest of the range of motion I wouldn’t worry too much about it.

When you think you are incapable of continuing an exercise in proper form, keep trying for a few seconds any way. If after a few seconds the weight still isn’t moving, then you can be certain you’ve achieved MMF. This is a little different if you’re doing static holds, timed static contraction, negative only, rest pause, and some others, but that’s something I cover in Elements of Form.

If you do drop sets, you would certainly know. When dropping 10% of the resistance after RM is reached and the next repetition is extremely difficult, I think you truely reached MMF.

Poiu,

Inability to continue positive movement after attempting to do so with maximum effort in strict form for at least five seconds is enough to know you’ve achieved momentary muscular failure. I do not recommend drop sets in most cases as it increases the volume of work without actually increasing intensity.

As usual, a thoughtful post. In particular, I appreciated the fact that you addressed the claim – silly on its face – that “training to failure is training to fail;” a point I’ve seen made a number of times by a retired economics professor, now of some fame in the ‘blogosphere’

Hey Will,

Yeah, it’s pretty silly and shows their ignorance of the real objective of exercise.

I only have one issue with MMF and was wondering if you can clear it up for me. It’s hard to put it into words clearly but it seems to me that going to MMF provides you with even less information than the alternative like you mentioned in your first point. As an example, let’s say that I perform sets in a typical strength training manner where I always leave two reps “in the tank”, which allows me to perform anywhere from 5-10 sets of a very heavy weight. Knowing this, if I performed the same exercise HIT-style, I would only produce a single good set of maybe 8 reps, but the CNS burnout would sabotage any further sets, that’s why MMF is done single set to failure.

My question is then, isn’t MMF feeding us the wrong information? It produces accelerated fatigue but at less volume, which to me seems like it terminates workload prematurely.

Can you clear up any thoughts on this for me? Because I always feel odd doing a single set of 8 when I know I could have done as many as 5-10 sets of 5 with that same weight.

Vartan,

Results from training have far more to do with intensity than volume of work. While training harder produces better results, doing more exercise than necessary to address all the major muscle groups does not, and beyond some point increases in volume and frequency will produce worse results. By sacrificing intensity of effort for the sake of doing more sets you reduce the effectiveness and efficiency of your workouts.

Hi Drew,

Thanks again for bringing more attention to the paper. I’m glad you addressed the criticisms of training to MMF, especially the idea of CNS burnout. It has always appeared that the ones bringing up this point as an argument against MMF were continuing with their high volume/frequency approach whilst trying to acheive MMF every time. Just a complete lack of understanding basic stress physiology and the stimulus-recovery-adaptation relationship.

Thanks

James

Hey James,

Thanks. It amazes me how some people can be oblivious to something so obvious. Hopefully more people read the paper and get it. What would be even better if other researchers take note and start designing their studies more sensibly.

I’m perfectly happy training to MMF, but it’s principle exercise I get in a week, so I’m happy to wait out the recovery period. But I got to thinking:

Given that training to MMF requires longer recovery periods, I wonder whether it is best for those training for other sports. If you exhaust yourself in the gym, to the point where you need 3 – 5 days to fully recover, could this adversely affect your ability to practice and perform your chosen sport? In which case, training to less than failure might be more beneficial for your chosen athletic performance even though your strength gains might be compromised, and you may have to spend longer in the gym doing multiple sets.

What’s your opinion on this? Have any studies been done?

Ian,

An athletes strength training program needs to be modified to take into account the demands and requirements of practice and competition, as well as their individual response to training. This may be the case for in-season training with some athletes depending on the volume and frequency of practice and demands of the sport. While this may be an argument for submaximal training in the case of athletes who had a harder time recovering enough to perform well in practice, there would still be no reason to add more sets. More sets would be more detrimental than more intensity with regards to recovery.

Hi Drew-I recently read your interview with Ellington Darden (done several years ago). In that interview he talks about NTF (not-to-failure) workouts, which he incorporates here and there in the workout programming in his book “The New High Intensity Training”. In the interview he says that if those who do HIT only once per week would also include a NTF workout, they’d likely make better progress. In the book he says NTF workouts may facilitate recovery. While traditional HIT advocates seem to say periodization is unnecessary, Darden seems to be meeting the idea half-way with the periodic NTF workout. What are your thoughts on this?

Thomas,

If an increase in workout frequency made a significant difference in a trainee’s progress either their starting frequency was too low to take advantage of their recovery ability or they improved their recovery ability by eating and sleeping better and reducing stress, and the results would have nothing to do with stopping their sets short of failure. I suspect any benefit would be more psychological than anything else.

I still can’t get rid of the idea of multiple sets completely.

Drew what do you think about such a combo: 5/3/1 done with just prescribed numbers (like “just 5” not “5 or more”) – and then as the “accessory work” – high intensity stuff with some pulling and pushing.

Assuming traing twice a week, do you think this could work?

Zbiggy,

While there is no need for multiple sets, the total volume of work you’re talking about would not be excessive. The problem with this is the same mentioned in number 2 above, however. If you do it this way, I’d recommend doing it in rest-pause fashion, not resting more than ten seconds between the sets (making it one big rest pause set) and keeping the rest time consistent between workouts for objective comparison.

Drew, if you’re cutting would you still recommend training to failure?

Some advocate training RPT when in a caloric deficit – not mentioning names – where only the first set is trained to failure; this set being maximal.

Steve

Steve,

Yes, I still recommend training to failure. Also, different people defined rest pause training differently, so I’m not sure if you mean performing a set of regular repetitions to failure followed by a short pause, then attempting more repetitions, or pausing for a specified time between each repetition of a set (usually around five seconds). Both have their uses, but rest pause and training to momentary muscular failure are not mutually exclusive. During rest pause training momentary muscular failure occurs when you can’t complete another repetition in good form after the prescribed pause duration.

If similar rep ranges are used rest pause might be a good way for people having difficulty training on a calorie deficit to continue using their usual loads, although I’m not sure how much of a difference it would make. As an experiment I once trained a pair of identical twins for eleven weeks, one with regular repetitions the other with rest pause. Despite instructing them to increase their calorie and protein intake they both lost fat, indicating a calorie deficit. I don’t have the data in front of me right now but the two of them had very similar muscle gain and fat loss, only a few pounds both ways.

@zbiggy-the 5/3/1/ thing is a Jim Wendler workout, right? Actually, It seems to me that his 5/3/1 workout is HIT compatible, due to the fact that the first 2 sets out of the 3 (one week is 5/5/5, next is 3/3/3, and finally 5/3/1) really are just warmups and the last one is 5, 3 or 1 plus any more that you can do (all are done on a % of the one rep max, but this doesn’t really matter as the last set is a max effort set). He does recommend stopping shy of failure, but that’s just a hat tip to power lifting dogma. Where he departs drastically from HIT is in assistance exercises, as in 5 sets of 10 lunges, etc.

The journal article these comments refer to appears outstanding in my non-expert opinion. Your commentaries have been exceptional as well. i look forward to future threads on this subject.

Chris

Thomas – yes of course I meant Jim Wendler’s 5/3/1

As for “powerlifting dogma” – I guess they don’t go for real failure that often because they train 4 days a week (as in the basic Wendler’s template) and it could be hard to keep going that way.

But what do I know, I’m 40 and started lifting weights as late as at 39

I saw Doug McGuff’s workouts on youtube and this is something that would fit more in my present life situation but on the other hand – it’s hard to work out on my own counting seconds etc. and another thing – I want to see real progress in say military press and can this superslow stuff with machines show it?

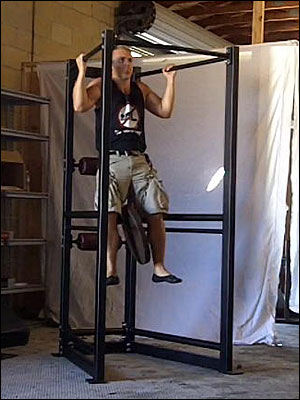

And Drew is the man who counts reps, works with free weights and shows perfect form as seen on the UXS demo so I guess this (plus maybe elements of 531) is the way to go for me. I have bought “High Intensity Workouts” (good ideas to choose from) and wait for US dollar to drop a bit and will buy “Elements of Form” and maybe switch to HIT

Hi Drew,

Another great article I agree with your comments it is not the principle of MMF that is wrong it is the “application”, the continued application of MMF over a long period of time is the mistake people make. When I first started training HIT I overtrained very quickly trying to train 3 days per week with every set going to MMF – lesson learnt and HIT is a learning process.

I have mentioned this to you before that those people who do these “supposed scientific weight training research” are not applying MMF in the overall context of a long term training program. Simply put if I had someone come in 4 or 5 days per week training MMF every sessions overtraining would occur after the first couple of sessions.

I am not sure why MMF is so controversial when weight training Hill and Lupton showed that the higher the exercise intensity, the higher the blood lactate levels and the greater the oxygen debt in recovery. A lot of the research that Hill and Lupton conducted was in relation to running but from their comments to me this means that your leg muscles would be working towards MMF.

From my understanding all Arthur Jones did was invent a machine that could give us a higher level of intensity using resistance training and to ensure the level of intensity was high enough train the muscles to MMF. The same as Hill and Lupton suggested with the leg muscles for running. I hope I haven’t rambled too much.

Thanks

@zbiggy-They work out 4x per week but have you seen the volume, especially on the assistance work? So I’m not sure many average individuals training 4x per week are going to do that well on that kind of volume in the long run. Reduce the workout volume by 1/2, take the frequency down to 3x per week and do those few extra reps to failure will likely get just as good (if not better) results in much less time-which is the real beauty of HIT. And by the way, if you want to get good at doing military presses, then you have to do them-forget the machine presses. And you’ll never get really good doing squats if you only do leg presses (same goes with bench). There is no magic in Body by Science, TUL or machine training. Free weights work fine too-lifters have been getting big and strong on them for decades. Basic, hard, lower volume and less frequent training is the way to go (it’s all relative of course).

Hey Drew,

Do you think its a good idea to perform an exercise to MMF even when one is sick with say a cold. I’m just thinking the stress on recovery would be too much and some of us like to still go to the gym even when we are a little bit under the weather.

Matt,

No. If you have a cold you shouldn’t be working out at all.

Hi Drew-I’m wondering if you’d comment on the research review over at Lyle McDonald’s site entitled “Strength and Neuromuscular Adaptation Following One, Four and Eight Sets of High Intensity Resistance Exercise in Trained Males.” It seems to me the review shows that practice, especially on a complex exercise such as the squat, makes for better strength gains over the short term due to neuromuscular adaptation, not necessarily myofibril hypertrophy (although they did show that the high set group gained more weight). Essentially, the more practice the better, in the beginning. It would be interesting to see how these gains end up over the long term, maybe 6 months to one year, on each protocol. I cant imagine an 8 set, to failure, squat workout being sustainable for long (or even 4 sets). Lyle does make a great point about the time factor, which I believe is the real benefit to HIT.

Hey Thomas,

I’m familiar with the study and while something like that may be beneficial for the short term for beginners due to the neural adaptations, the volume would have to be cut back as intensity increased and resistance progressed to avoid overtraining. It would be better not to do that with beginners though, because you’d just end up confusing most people. As simple as it is, many people seem to have a hard time understanding the need to reduce the volume of training as intensity increases.

Drew-I agree. there is no way in hell a person can keep up an 8 set, each set to failure routine (or even 4 sets), twice per week. I think the body is great at short term adaptation no matter what the stimulus-you’ll see some improvement in the beginning on almost any routine. But inevitably you get into the later stages of the GAS and everything goes to hell quickly (I’ve been there), if you don’t back off. Seems this study really doesn’t tell us anything about effective training over the long term. I do see how this info can be useful for people who want very quick, short term results (ie. quick training for boot camp, get in shape for a movie role, etc.)

HIT is a precise way to build strength, muscle & endurance. Is there an equally precise method of ‘every-day’ low intensity exercise for stress management?

Mark,

I’m not an expert on stress management, but in my experience few things work as well as a trip to the gun range.

For the last four weeks I have been attempting to do high intensity work outs one day a week as recommended by you and Dr. Doug McGuff, I have seen gains in the amount of weight I am able to push/pull, which is good. For four or five days after I train, my body is very soar.

I just had a question about soarness and if it is normal to always feel soar with muscles aching and feeling tight? Is stretching something to combat the soarness?

When I use to work out 3 or 4 days a week, I would rarely feel this soar. I assume this means my muscles are really being shocked and growing, but I am just curious what your opinion is.

James,

The soreness is normal when changing exercises or training methods, and especially when increasing exercise intensity. Soreness is not an indicator of exercise effectiveness, however; there are a lot of things that can cause soreness that stimulate no physical improvements at all. If the soreness is really bad it can be reduced by repeating the exercise that caused the soreness. Normally you would want to wait until your next workout for full recovery, but if the soreness is bad enough performing the exercise sooner will help.

Hi Drew,

The new site looks great, you mentioned in the above post that soreness is not a indicator of exercise effectiveness I totally agree with this statement. The number of times I hear people say that I told my personal trainer (used loosely) that the workout did not make me sore and than the trainer proceeds to put the client through some type of ridiculus training session. Besides new or unfamilar activities could muscle soreness occur because of continually recylying of the lower order muscle fibres due to steady state training (low intensity). The higher order muscle fibres are actually never effectively engaged or if they are it only happens after a significant number of sets. By the time the higher order fibres are engaged the chemicals at the muscular level are completely depleted. Do you think that muscle soreness could be from chemical depletion at the muscular level?

Steve,

Delayed onset muscle soreness appears to be most strongly related to microtrauma, although that doesn’t explain why it would decrease despite increases in training intensity over time. I also don’t think has as much to do with energy substrate depletion or metabolic byproducts due to the time frames.

Once again great post. Perfect form is so crucial when training to MMF. We call it a ‘leak’ if form breaks down towards MMF. Even a little wiggle at that moment can send the wrong message, that the force can be diverted, and misses the fullest stimulus.