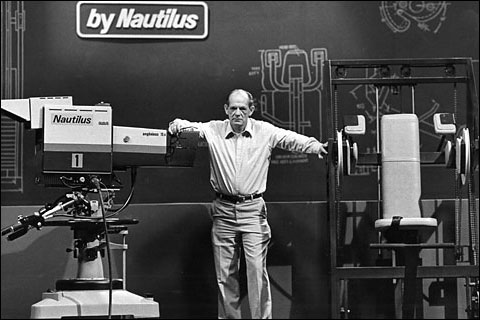

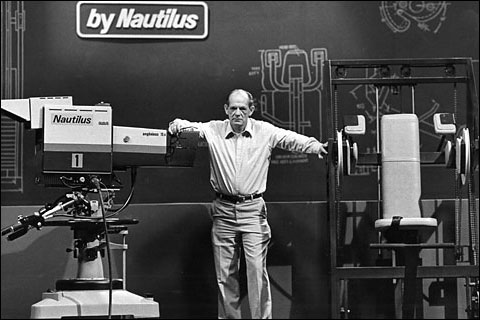

- Arthur Jones in the Nautilus Television Studio

Nautilus inventor and fitness industry pioneer Arthur Jones was born on this day, November 22, in 1926. He revolutionized the fitness industry in the 1970’s with his Nautilus machines and his articles telling people to “…work harder, but very briefly and infrequently” at a time when many bodybuilders were working out twice daily, six days per week.

I first met Arthur in spring of 1997 at a MedX presentation at the Sheraton in Orlando which Jim Flanagan invited me to. After that, we communicated by phone for several years and during occasional visits to his house in Ocala with David Landau and others. It was an honor and a privilege to have known him, and I am grateful for the opportunity.

I learned a lot during these discussions with Arthur, but most of what I learned from him was through reading his Nautilus Bulletins and his Iron Man and Athletic Journal articles. When I worked as a personal trainer for SuperSlow founder Ken Hutchins I helped him move several filing cabinets full of files, articles and publications including much of Jones’ writing. With Ken’s permission I spent hours reading through these, including a copy of the previously unpublished Bulletin 3.

Although I had already read many books on high intensity training by experts like Mike Mentzer and Ellington Darden as well as Ken Hutchin’s SuperSlow technical manual, few of them were as comprehensive or covered as much ground as the Nautilus Bulletins.

I just recently spent a lot of time re-reading these, and although there are a few things in them Arthur later changed his mind about and a few statements that turned out to be wrong, the majority of what he wrote back in the early 1970’s was dead on. The following are just a few of my favorite quotes from Bulletins 1 and 2 (1970, 1971):

On training hard,

“…work harder, but very briefly and infrequently”

“In general, the harder an exercise is, the better its results will be; don’t look for ways to make exercises easier—look for ways to make them harder.”

“…more exercise will never produce the results that are possible from harder exercise…”

“If constant efforts are made in the direction of true progress, if you try to do more reps in each set of every exercise, and if you always increase the resistance in proportion to your strength increases, then growth can be, should be—and in most cases, will be—very fast; not fast only for beginners, but fast for anybody, regardless of his existing level of strength or muscular size, right up to the top level of momentarily-existing potential.”

On workout volume and frequency,

“Best results will always be produced by the minimum amount of exercise that imposes the maximum amount of growth stimulation.”

“…the body can withstand any possible “intensity” of exercise, so long as the amount of such exercise does not exceed the limits of the recovery ability.”

“All of the evidence clearly supports the contention that the “intensity of exercise” should be as high as possible—and that the “amount of exercise” should be limited to the absolute minimum that will produce the desired growth stimulation.”

“If you train properly, you don’t need an actually large “amount” of exercise; more than that, if you train properly, you can’t stand much exercise.”

“If only a few actually very simple points are understood—and applied in practice—then almost all trainees can reach their individual limits of muscular size and strength very quickly, and as a result of brief, infrequent workouts…”

On exercise selection and training routines,

“If a proper selection of exercises is made, then only a few movements are required to develop almost the ultimate degree of strength and muscular size.”

“Properly performed, even a very few basic barbell exercises will produce good results—improperly performed, and no amount of exercises or sets will produce equal results.”

“For best results from exercise, all of the major muscular structures should be worked—all of them; you certainly can build large arms without working your legs—but you will build them much larger, and much quicker, if you also exercise your legs.”

“…human muscular structures are capable of an almost infinite number of individual movements if we consider all of the possibilities and combinations, and attempting to provide a separate exercise for each of these possible movements would certainly be impractical at the very least—but if we consider only major movements, then the number of functions are such that “almost all muscles are involved in almost all movements” (at least in gross terms and in a general sense), it becomes obvious that an actually very limited number of exercises can provide the required work for all of the muscular structures.”

On nutrition,

“A man on a program of heavy physical training will obviously require enough extra calories to supply the energy required by such training—or, at least, he will if he hopes to maintain his existing bodyweight; and if he wishes to gain additional bodyweight, then he will require even more in the way of nutritional factors. But such requirements can come—and, indeed, should come—from a fairly normal diet; such a diet should be well rounded in makeup, and should contain enough protein for meeting the requirements of the moment. Absolutely nothing else in the way of a special diet is required.”

On abdominal training,

“…if you train the rest of the body properly, then the abdominal area will take care of itself. The billions of sit-ups and leg-raises that have been performed by millions of trainees have been almost a complete waste of time and effort…”

“You can build the muscles of the midsection by performing a reasonable amount of intense exercise for the directly involved muscles, but no amount of exercise for these same muscles will help to reduce fat in that area of the body so long as a positive calorie balance exists—a much better approach to the problem is to reduce the food intake as much as possible while performing a reasonable amount of exercise for all of the muscles of the body.”

And the following are a few favorites from Bulletin 3 (1973):

“In later chapters covering exact styles of performance, you will be informed that movements should be “as fast as possible in good form” in many exercises. But many people overlook the most important part of that sentence…in good form.”

“…the most two important factors in exercise may well be individual potential… and quality of coaching.”

“If the intensity of an exercise is below this threshold, below a certain level, then you can train for years with nothing in the way of resulting strength increases. But if the intensity is above a certain level, then strength increases will be produced rapidly. And it seems that the higher the intensity, the faster the strength increases will be produced…or, at least, they will be if you don’t make the mistake of overtraining, of training too much.”

These quotes are as true today as they were nearly four decades ago, and following or ignoring this advice can mean the difference between rapidly maximizing your muscular potential or wasting hundreds of hours in the gym year after year with little or nothing to show for it. Have a favorite Arthur Jones quote or a memory of Arthur to share? If so, please comment below.