If the advent of Nautilus and high intensity strength training in the 1970’s was a renaissance in exercise, the current rising popularity of so-called “functional training” is a return to the dark ages.

In her recent New York Times article, Fitness Playgrounds Grow As Machines Go, Courtney Rubin writes,

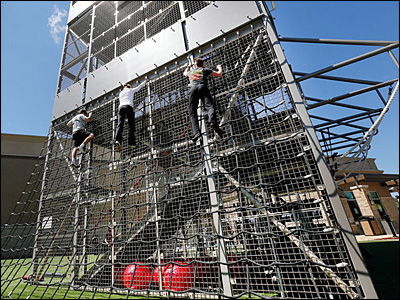

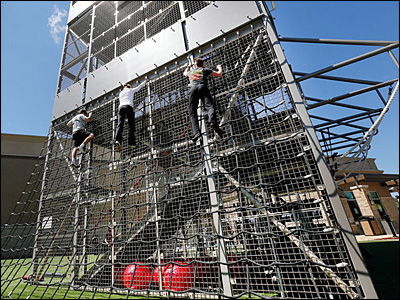

Simple exercises with no-tech equipment (call them paleo or playground exercises, depending on how much fun they are) have long found disciples at niche gyms and in movements such as CrossFit. But in the last year and a half, major health-club chains have begun making hefting sandbags and shaking 25-pound ropes the standard, ditching the fancy weight machines that have dominated gym floors for more than 30 years.

In other words they’re replacing productive, efficient, and safe tools and methods with less productive, inefficient, and riskier ones.

The so-called “functional training” trend is primarily based on the beliefs that exercises must mimic other physical activities like daily living or vocational tasks or sports skills to improve your ability to perform them and that exercises should be performed on unstable surfaces or unilaterally to improve balance and more effectively strengthen your “core” muscles.

These beliefs aren’t just wrong, they are completely backwards.

Your functional ability – how well you are able to perform various physical activities – is determined by several factors. Some of these factors, like your muscular strength, cardiovascular and metabolic conditioning, and flexibility are general; improving them helps you better perform any physical activity. One factor of functional ability, skill, is specific; improving your skill in a particular physical activity only helps you better perform that specific activity.

While the number of possible body movements a person can perform is practically infinite, all of them are just different combinations of a few basic joint movements. Regardless of the specific exercises performed, as long as you strengthen all the muscle groups which produce those joint movements your general ability to perform any movement will improve. For example, it doesn’t matter that the exercise movement performed on a leg extension machine does not resemble some other movement; if your quadriceps are stronger your ability to perform any movement involving knee extension or requiring you to resist knee flexion will improve.

Since the improvements in functional ability from strength gains are general there is no advantage to performing exercises in a manner that mimics other activities. Instead, exercise movements should be based on the requirements for effectively and safely working specific muscles or muscle groups to stimulate increases in strength. This includes both compound (multi-joint, linear) and simple (usually single joint, rotary) or so-called “isolation” exercises. As a corollary, the tools used for exercise should be appropriate for or designed around these movements, and this can include anything from low-tech barbells and dumbbells and basic bodyweight apparatus to high-tech machines.

Attempting to mimic another activity with exercise usually results in inefficient muscular loading and can interfere with the skills of the movement being mimicked (negative skill transfer). Attempting to mimic sport movements involving rapid acceleration during exercise also unnecessarily increases the risk of injury.

If you want to improve your ability to perform a specific movement don’t try to mimic it during exercise; instead learn and practice the movement as you would normally perform it, and if it involves a tool, instrument, or sporting implement practice using that exact tool, instrument, or implement.

Performing an exercise on an unstable surface will improve your skill at performing that specific exercise on that unstable surface but will not improve your skill in other balance tasks. Also, activation of the target muscle groups and the stimulus for strength increases is reduced, not improved, when exercise is performed on an unstable surface. The more focus required to maintain your balance the less you can devote to contraction of the target muscle groups.

Proponents of so-called “functional training” often claim exercise on unstable surface is more effective because it involves more muscles. They fail to distinguish between muscular involvement and efficient loading. Just because a muscle is involved in an exercise in some manner does not mean it is subject to loading sufficient to stimulate significant increases in strength and size. Since maintaining balance requires the center of gravity of the body to be maintained directly over its base the muscles involved in balance work against minimal moment arms, thus minimal resistance and receive little exercise benefit.

As an example of this myth, the article quotes Adam Campbell, fitness director for the Men’s Health brand as saying,

…machines like the leg press strengthen muscles, but asked: “What’s the real logic in sitting or laying down to train your legs?” Functional fitness is “far more bang for your buck” because it works multiple muscles simultaneously, he said, providing better overall strength and mobility, and a higher calorie burn.

Adam Campbell doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

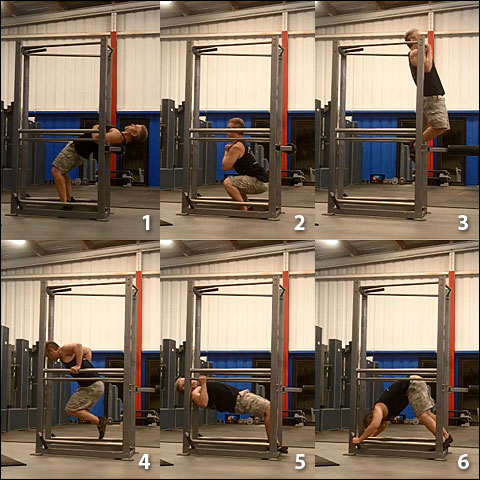

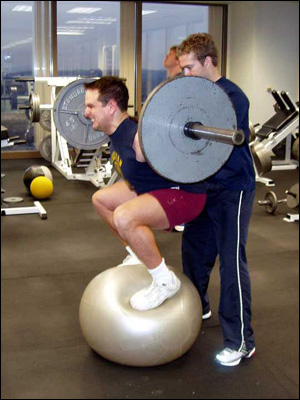

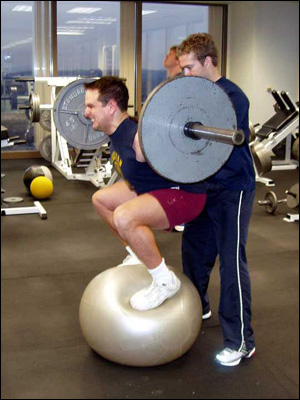

The logic of sitting or laying down to train your legs is these machines allow the target muscles to be loaded more efficiently and more safely than conventional barbell movements, and much more effectively than squatting on a ball like the idiot pictured above. While many so-called “functional” exercises involve more muscle groups than machine exercises or conventional barbell exercises they do so in a manner that loads those muscles haphazardly and inefficiently.

Exercises performed in a manner that efficiently loads the targeted muscles, using equipment designed for this purpose will provide “better overall strength and mobility” than exercises which mimic other movements or involve unstable surfaces or spread the work over a larger number of muscle groups in a way that loads them inefficiently (like exercise “complexes” which combine several different movements into a single exercise).

And, while exercising to burn calories is generally a waste of time, the calories burned during or metabolic demand of an exercise are not determined solely by the amount of muscle involved but also how hard the involved muscles are working. If you don’t experience a tremendous metabolic demand performing a circuit of machine exercises you aren’t using them correctly.

Later, Josh Bowen, formerly of Urban Active is quoted as saying,

Gyms are way out of the times if all they have is machines.

Bullshit.

A gym with nothing but forty-year-old first and second generation Nautilus machines is way ahead of any gym whose equipment consists mostly of so-called “functional training” staples like stability balls, ropes, medicine balls, truck tires, plyo boxes, and kettlebells.

After a few more paragraphs of ignorant machine bashing the author quotes several people on how odd so-called “functional training” looks to people used to more conventional training. One person is quoted as saying his wife “looks like a circus clown” when doing her “functional” exercises. Another worries people are watching him thinking it’s the dumbest thing they’ve ever seen.

While I have seen and heard about people doing a lot of really dumb things over the years, and so-called “functional training” might not be the dumbest, it is definitely close to the top of the list. It violates motor learning principles, violates principles of safe and efficient muscular loading, and gives people less exercise benefit with more risk. Forget about looking stupid, getting injured because you lose your balance and fall or drop something on yourself is a great way to quickly (and in some cases permanently) reduce your functional ability.

Like the guy who was badly injured when he lost his balance and fell through a plate glass window a few years back because his idiot trainer had him doing dumbbell flys on a stability ball.

Like the college quarterback who is now paralyzed because he broke his back when he lost his balance doing weighted step-ups.

Like the CrossFitter who smashed his foot doing sledgehammer swings.

If you want the greatest possible improvement in general functional ability don’t follow the so-called “functional training” crowd. Work hard, progressively, and consistently on a few basic exercises involving all the major muscle groups. Move slowly during exercises to keep consistent tension on the target muscles and minimize risk of injury, but move quickly between exercises to maximize cardiovascular and metabolic conditioning. Separately from your workouts, learn and practice the correct performance of the specific sport or vocational skills you want to improve at.

And finally, if other people in the gym are doing so-called “functional training” exercises, make sure to give them plenty of clearance so when they do lose their balance or grip and fall, or drop something heavy, or lose control while swinging or throwing something, they don’t reduce your functional ability in the process.