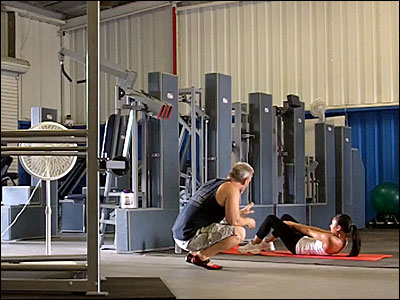

Even if you are knowledgeable about a subject, teaching it to others is impossible if you are unable to effectively communicate what you know. As you are aware if you are a professional personal trainer or have trained inexperienced friends or relatives, sometimes this is not as easy as it sounds. Teaching is largely a matter of effective communication, and if you wish to improve your ability to teach you must learn how to convey the knowledge you possess in a way your clients or trainees can easily grasp and relate to.

Define Your Terms

While terms like quadriceps, supinate and concentric are familiar to those knowledgable about exercise, they are not so well known by much of the population. Whenever possible, it is best to use common rather than technical terms. If it is necessary to use a technical term to explain a particular principle or concept, first define that term and explain it’s meaning. After you have explained something always ask if the trainee has any questions or if there is anything they are unclear about, to ensure they understand before moving on to new information or information which builds on what you have just taught them.

The main categories of terms to be defined are those related to anatomy, movement, and equipment.

For example, if we were to instruct a trainee in the performance of a front-grip pull down, we would first point out and name which muscular structures were involved in the movement and what functions those structures perform, so they know what to concentrate on during the exercise. Then if we tell them to focus on pulling their elbows down and back and on contracting their lats, they know exactly what we mean.

We also need to define terms related to movement such as positive, negative and turnaround, and in the case of the pull down, explain that when we say lifting or lowering we are referring to the movement of the weight stack or resistance source, and not the handle or the trainee’s arms so there is no confusion. This must be explained before the exercise, since many people will assume you are referring to the movement of their body when you say lifting or lowering, which in this case would be the opposite of the direction the weight stack is moving.

It is also important that the trainee be familiar with the terms defining any part of a machine which they will be interacting with, so they understand instructions related to actions involving that part. This is especially important when instructing the trainee on how to properly enter and exit a machine where they may be using a part of the machine for support or as a step while moving in or out or while positioning or aligning themselves.

Give Precise, Detailed, Concise Instructions

Instruct the trainee on every aspect of the exercise from start to finish. Do not assume a novice trainee even knows how to properly enter or exit a machine or load into an exercise such as a barbell squat. Instructing the novice on how to properly enter and exit a machine or pick up or load under a barbell is just as important for their safety and the effectiveness of the exercise as instructing them on how to properly perform it. For example, a very simple but important part of the proper exit procedure for any leg machine is making sure that the subject has both feet on the ground and away from any part of the machine they could trip over before attempting to stand out of the machine.

Do not assume the trainee has any prior knowledge of the exercise they are being instructed in, and provide very specific details in how they are to position or align themselves and how to perform the movement. For example, when instructing someone on a front-grip pull down or leg press, don’t just tell them to grab the handle or place their feet on the pedal. Tell them exactly where and how you want them to grip the handle or where and how you want their feet positioned on the pedal, being as specific as possible.

Before the trainee begins performing the exercise, ask if they have any questions and make sure they understand exactly what they are supposed to do.

While such detailed instruction might seem excessive, it is essential for safety’s sake. Safety should be the highest priority of facility owners and professional trainers. Whenever instructing someone in the performance of an exercise every possible measure should be taken to ensure the safety of the person performing the exercise and everyone around them. Nobody wants their members or clients harmed, or to end up involved in a law suit.

In addition to giving precise, detailed instructions, it is important to phrase your instructions in the proper order. While being instructed in the performance of a new exercise, the trainee should be paying close attention to your instruction, and will often react immediately to anything you say. If you do not properly phrase your instructions, this can lead to confusion. Before you tell them what to do, tell them when or at what point during the movement you want them to do it, and how.

Suppose you are instructing a client in the performance of a chest press for the first time and you are going to tell them to perform a turn-around, or smooth reversal of direction immediately before lockout. If you say, “Begin to turn-around slowly as you approach the end point. ” they might respond immediately when they hear the first words, “begin to turn-around…” and quickly reverse direction halfway through the movement. A better way to phrase it would be “As you approach the end point, slowly begin to turn-around.” This way they will know when and how they are supposed to perform the action before they know what that action is, and will not act prematurely.

While some directions will require more words than others, it is always best to be as concise as possible while instructing someone during an exercise. If you can say something with fewer words without compromising the precision or exact meaning of the message, then do so. For example, instead of saying, “Try to move a little slower as you begin the repetition”, say “Slower starts.” Assuming that you have already explained to the subject what you mean by starting point or start, this is more efficient and less distracting. Considering the example in the previous paragraph, once the client has learned the term end point and knows the end point for the exercise being taught, you can simply say “As you approach the end point…” instead of the wordier and less efficient “As you approach the point where your elbows are almost fully extended…”

Emphasize the Positive

There are often several ways to say the same thing, some positive, and some negative. When instructing a novice it is important to consider that they may feel somewhat awkward while learning a new exercise and might become frustrated if they’re having difficulty learning how to perform it properly. To avoid causing further frustration or irritation it helps to phrase things in a positive manner rather than as criticism. Instead of telling them what they’re doing wrong, tell them how they should be doing the exercise, or how they can improve their performance.

For example, instead of saying, “you’re moving too fast,” which sounds like criticism, say, “move slower” which is simply an instruction. Instead of saying, “your grip is too wide,” tell them exactly where and how you want them to position their hands. Phrase your instructions in a positive rather than critical manner whenever possible. After the exercise or workout, point out all of the things the subject performed correctly and commend them on any improvements in their form before discussing any areas that need work. This is especially important when working with people who don’t take criticism well or become agitated when they experience difficulty learning a new exercise or technique.

Because novices will often feel awkward and unsure of themselves, especially when learning exercises that require a greater degree of motor control, it is important to provide them with encouragement. The best way to do this is to let them know when they’re doing things right. Try to balance instruction with encouragement. Motivating someone to put forth their best effort during an exercise is just as important as teaching them to perform the exercise properly.

Effective Communication vs. Mindless Babble

It is unfortunate that most of what passes as exercise instruction in many gyms amounts to little more than mindless babble. I have observed many personal trainers over the years who not only know little of value about exercise, but are also incapable of effectively communicating what they believe they do know about the subject to their clients. I don’t consider such individuals to be personal trainers. A more appropriate title might be workout cheerleader orweight caddie. The following are examples of the kind of mindless babble I have heard from personal trainers in various gyms:

“Yeah, that’s it, keep going. Great! Come on! You can do another!!”

“Uh huh, good. Uh huh, good. Uh huh. Uhhhh, yeah. Uh huh”

“COME ON YOU F****** P****!! PUSH!! PUSH!! HARDER!!! HARDER!!!!”

“That’s it, squeeze! Squeeze! Feel that burn!”

While some might find this encouraging it is not exercise instruction. Yet this is the kind of inane chatter many people waste their money on when they hire the typical “personal trainer.” Don’t allow yourself to make the same mistakes. Clearly define your terms, give precise, detailed instructions, and phrase them carefully, concisely, and in a positive and encouraging manner.