Drew: Could you tell the readers about how you came to be involved with both high intensity training and the sport of powerlifting?

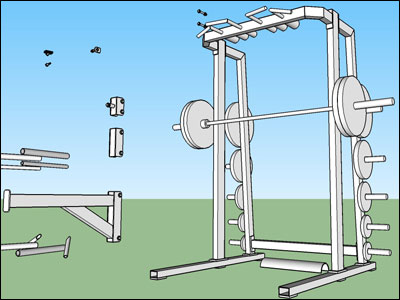

Doug: Hmmm. Well, basic weight training exercises came first at age ten. My dad showed me the barbell press, the barbell curl, the static chin up, and later when I was strong enough, the dynamic chin up. At age 13 I graduated to a friend’s garage where we did bench press, squats, curls, and overhead press. My legs got really strong and I got tired of cleaning the weight and putting it on my shoulders for squats (we had no rack in the friend’s garage). I asked for and received a YMCA membership from my parents. Three days a week, after school, I would walk barefoot in the snow, uphill, to the Y. I now had a squat rack and I focused on this lift. Bench presses and lat pulldowns were also done.

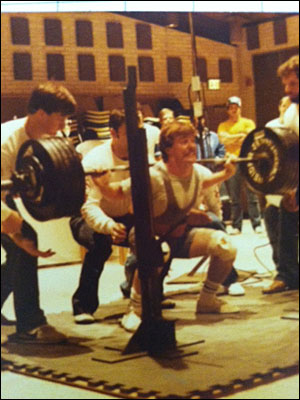

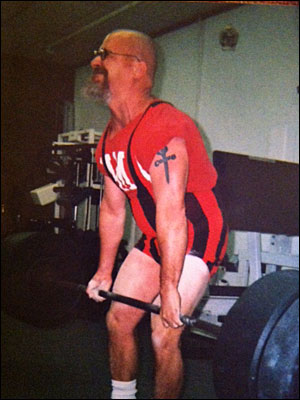

A few older lifters took notice of my perfect attendance and introduced me to the deadlift. I loved it. And these lifting mentors from 1976 remain friends of mine to this day. Just recently one of them helped me repair one of my air conditioners at my gym. The old guys decided I should enter a powerlifting meet, so they took care of all the paperwork and entered me in the Louisiana State meet, which I won as a 132 lb’er. Fuck! I was hooked! (In later years I won the title at 148 lbs and 165 lbs).

In my early college years I came upon some of Arthur Jones’s early writings in Athletic Journal. I liked his writing style. He reminded me of my dad, probably some Great Santini type character. Over the next few years I read more and more of his articles, and reading between the lines, discovered that high intensity training had less to do with training on Jones’s Nautilus equipment and more to do with just training harder and briefer. I decided to adapt his philosophy to my powerlifting training. I did not want to spend hours in the gym. There were girls to meet. There was beer to drink. There were cars to drive. There were guitars to play…

Drew: How did you go about adapting Arthur Jones’ high intensity training philosophy to powerlifting?

Doug: I had only barbells available so I decided to model my training after Jones’s writings. Since I was lifting some pretty heavy weights at the time, I put in a few warm up sets (I like to call them “groove sets”) before I began a work-out. I would do a few light, non-taxing sets for lower body and upper body, and then get with it. An example would be this:

Squat: two or three warm ups of low reps

Bench press: same as above, then:

- Squat

- Weighted chin-up

- Bench press

- Weighted chin-up

- Bench press

- Shrug

- Dip

- Squat

On day two I would use a similar warm up for deadlift and overhead press and do the following:

- Deadlift

- Rest 2-3 minutes

- Deadlift

- Overhead press

- Leg press

- Close-grip bench press

Work outs never exceeded thirty minutes. I had things to do. Besides studying for my mathematics degree, I had a full-time job which I loved. I didn’t want to hang around the gym rats. They mocked me, but I didn’t give a shit. I was secretly seeing their girlfriends…

I kept meticulous records on large pieces of cardboard, along with a “backwards plan” on another piece of cardboard, targeting my projected lifts at meet time. These were nailed to the wall of my living quarters. Visitors to my small apartment figured me insane, which I probably was at the time.

As a contest neared, I would, of course, raise my weights and reduce my reps for each competitive lift, until I was working for a threatening three lift maximum. I never used a lifting suit in training, and only used old, worn out knee wraps. I never, ever, wore a bench press shirt. Fuck that shit! All my platform lifts were done in a cotton t-shirt, a tight lifting suit (of which I could get the straps up without help), knee wraps, and a belt from 1978.

Drew: It sounds like you kept things focused on the basics, without much in the way of accessory work. What are your thoughts on supplemental exercises for powerlifting?

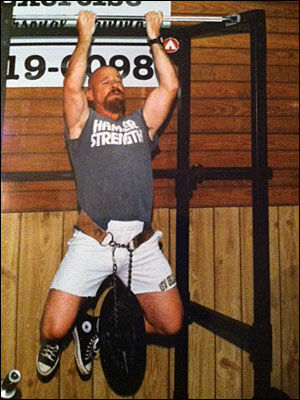

Doug: Yeah, always stayed with the basics. Supplemental exercises are fine, but be careful of overtraining and/or stagnation. A lot of guys swear by dips for help in the bench press. Some guys, myself included, get nothing from them. Grip work would be good if one is losing deadlifts at the top. When I began working in a plate loaded Hammer Strength gym, grabbing plates all day long, my weak grip problems vanished!

For deadlifts, Louie Simmons sells his reverse hyperextension machine, but a close look at it will show you it’s a retarded piece of equipment. A much better choice would be a Nautilus 2ST hip extension machine. The resistance is placed on the thighs instead of the ankles like Simmons’s piece. Leg presses are fine for squats, but don’t rely on them as a primary exercise. Big difference in leg pressing a lot of weight and shouldering a lot of weight. I like weighted chins for the lats. Understand that strong lats help keep the humerii tight and close to the torso when deadlifting, preventing the weight from swinging away from the line of pull. I dig shrugs, too, but mainly because girls ask if they can touch my traps.

Drew: What advice would you give someone who has been doing high intensity training and wants to compete in powerlifting?

Doug: I would tell experienced HIT trainees they should already have a good strength base to build upon. The next step is to learn proper form on the lifts. I’m from the old school, so I would bring them up slowly, emphasizing raw lifting (no supportive clothing) for the the first year or so. One doesn’t just load up the bar and throw things around.

That’s why I hate this CrossFit bullshit. Its ”philosophy” encourages bad form to get through the workouts. A few years ago I had two CrossFitters come in for some deadlift instruction. I asked to see their form and was horrified, screaming, “Stop, STOP! Goddammit! You fucks will not hurt yourselves in my gym!” I calmed them (and myself) down, taught them proper form, then took them through some productive deadlift sets.

One guy added 25 lbs to his best ever set of 10 reps. The other guy added 40 lbs to his best 10RM. Presently, I have a 52 year old client that I’m turning into a powerlifter, and he doesn’t even know it. Ha! I’m subtly throwing stuff at him and he’s handling it well, with precise form. HIT guys love this stuff!

Drew: I’ve worked with a few ex-CrossFitters; on the plus side they’re not afraid of working hard, but fixing their form can be a challenge. What advice would you give a powerlifter who has been doing more conventional training and wants to try high intensity training?

Doug: Powerlifters who want to try HIT… Hmmm… That can be difficult. Fortunately, the new powerlifting conventional wisdom is directed toward more infrequent training, so that’s good. But lifters still, in my opinion, spend way too much time in the gym, doing way too many sets. Fine with me. But there are other things to enjoy outside of gym time.

Back in the mid-nineteen eighties I trained a handful of neophyte lifters at my gym in Ruston, Louisiana. Each individual’s workout was done right after the other. Everyone was required to be in attendance to offer encouragement to the guy going through the workout. And then the next guy was up for his session. Each workout only lasted 25-35 minutes, mine included. In 1986 I took the guys to their first meet and it was amazing. Here we had my little crew of bartenders, nerdy engineering students, college professors, all squatting and deadlifting in the 400lb range, with one 165lb guy deadlifting 565. Good times.

Drew: In addition to the motivational benefit I think training a group like that helps because it gives everybody the opportunity to learn both by doing and observing, and some people seem to have an easier time getting some concepts that way. What specific advice would you give someone for squatting, benching, and deadlifting competitively, as opposed to doing them purely for exercise?

Doug: Well, obviously one is going to have to attempt one rep maximums on the competitive platform, so the lifter will need to get used to handling heavier loads. For myself and for the lifters I’ve helped out, I never attempt 1RMs in the gym. Heavy triples are the heaviest work sets I utilize.

If the lifter is going to lift in a federation that allows supportive lifting suits and bench press shirts, he or she is going to need to get used to lifting while “in the gear.” Personally, I loathe that shit. In fact, I never used a bench shirt and my squat suit was always one in which I could get the shoulder straps up without assistance. I remember watching Jim Cash and Dave Jacoby lifting at the 1984 World Championships, and both lifters wrapped their own knees and pulled up their own straps, and I remember thinking, “Wow! This is refreshing.” They didn’t need or want three or more handlers squeezing them in to super tight gear.

For the squat, I’ll have lifters do heavy, controlled “walk outs.” This is where you take a weight that’s too heavy to actually squat, and you unrack it, take a couple steps back, and set up as if you’re going to attempt it. After a few seconds of standing with the weight, you walk it back to the rack.

Similarly, heavy locked-out holds can be done on the bench press. If I calculate a lifter’s maximum bench press to be 350 pounds I hand off to him 370 or so and just have him hold it at arms length for a few second before getting it back to the rack. Both of these techniques can better prepare the lifter to be more at ease when it comes time to go for one-rep maxes at meet time.

Drew: Doug, thank you for a great interview, I know you’ve got a packed training schedule and appreciate your time. Any additional advice for those wanting to give powerlifting a try?

Doug: No problem, thank you for the opportunity. I love reminiscing about the better era of powerlifting. As for advice to those wanting to give powerlifting a try, I do have a few pointers:

- Find a good coach with gym and competitive platform experience. Learn the lifts from him (or her).

- Form and technique, form and technique. Practice with lighter loads. Learn the intricacies of each lift from start to completion.

- Spend the majority of your gym time training raw. If you do choose to lift using the tight suits, shirts, wraps, belt, etc., if you build a strong raw base, then the aids will be more effective.

- Find two or three other hobbies. If you’re going to train using a hybrid HIT/powerlifting routine, you’ll have extra time on your hands. Isn’t that great?!

- Learn to love the wearing of flat sneakers. I wear no other kind of shoe.

Drew: It was my pleasure. If readers have additional questions for Doug please post them in the comments below! Please be patient, as he has a very busy training schedule so he may not be able to answer questions right away.